The NorthStar

Polaris

Polaris

(Redirected from North Star)

Jump to navigationJump to search

| Database references | |

|---|---|

| Other designations | |

| Position (relative to α UMi Aa) | |

| Position (relative to α UMi Aa) | |

| α UMi B | |

| α UMi Ab | |

| α UMi Aa | |

| Details | |

| Orbit[1] | |

| Astrometry | |

| α UMi B | |

| α UMi Ab | |

| α UMi Aa | |

| Characteristics | |

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox | |

| |

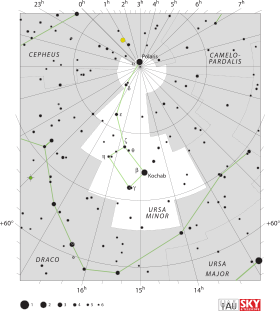

| Constellation | Ursa Minor |

| α UMi Aa | |

| Right ascension | 02h 31m 49.09s |

| Declination | +89° 15′ 50.8″ |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 1.98[1] (variable 1.86–2.13) |

| α UMi Ab | |

| Right ascension | |

| Declination | |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 9.2[1] |

| α UMi B | |

| Right ascension | 02h 30m 41.63s |

| Declination | +89° 15′ 38.1″ |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 8.7[1] |

| Spectral type | F7Ib[2] |

| U−B color index | 0.38[1] |

| B−V color index | 0.60[1] |

| Variable type | Classical Cepheid[3] |

| Spectral type | F6V[1] |

| Spectral type | F3V[1] |

| U−B color index | 0.01[4] |

| B−V color index | 0.42[4] |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −17 km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: 198.8±0.20 mas/yr Dec.: -15±0.30 mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 7.54 ± 0.11[5] mas |

| Distance | 323–433[6] ly (99–133[6] pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −3.6 (α UMi Aa)[1] 3.6 (α UMi Ab)[1] 3.1 (α UMi B)[1] |

| Primary | α UMi Aa |

| Companion | α UMi Ab |

| Period (P) | 29.59 yr |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 0.133″ |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.608 |

| Inclination (i) | 128° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 19° |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 303° |

| Semi-amplitude (K1) (primary) | 3.72 km/s |

| Mass | 5.4[7] M☉ |

| Radius | 37.5[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 1,260[7] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 2.2[8] cgs |

| Temperature | 6015[4] K |

| Metallicity | 112% solar[9] |

| Rotation | 119 days[2] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 14[2] km/s |

| Age | 7×107[10] years |

| Mass | 1.26[1] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.04[1] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 3[1] L☉ |

| Age | 7×107[10] years |

| Mass | 1.39[1] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.38[4] R☉ |

| Luminosity (bolometric) | 3.9[4] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.3[4] cgs |

| Temperature | 6900[4] K |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 110[4] km/s |

| Age | 7×107[10] years |

| Component | α UMi Ab |

| Epoch of observation | 2005.5880 |

| Angular distance | 0.172″ |

| Position angle | 231.4° |

| Component | α UMi B |

| Epoch of observation | 2005.5880 |

| Angular distance | 18.217″ |

| Position angle | 230.540° |

Polaris, North Star, 1 Ursae Minoris, HR 424, BD +88° 8, HD 8890, SAO 308, FK5 907, GC 2243, ADS 1477, CCDM J02319+8915, HIP 11767, Cynosura, Alruccabah, Phoenice, Navigatoria, Star of Arcady, Yilduz, Mismar | |

| SIMBAD | α UMi A |

| α UMi B | |

Polaris (/poʊˈlɛərɪs/), designated α Ursae Minoris (Latinized to Alpha Ursae Minoris, abbreviated Alpha UMi, α UMi), commonly the North Star or Pole Star, is the brightest star in the constellation of Ursa Minor. It is very close to the north celestial pole, making it the current northern pole star. The revised Hipparcos parallax gives a distance to Polaris of about 433 light-years (133 parsecs), while calculations by other methods derive distances around 30% closer.

Polaris is a triple star system, composed of the primary star, Polaris Aa (a yellow supergiant), in orbit with a smaller companion (Polaris Ab); the pair in orbit with Polaris B (discovered in August 1779 by William Herschel).

Stellar system[edit]

Polaris components as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope

Polaris components as seen by the Hubble Space TelescopePolaris Aa is a 5.4 solar mass (M☉) F7 yellow supergiant of spectral type Ib. It is the first classical Cepheid to have a mass determined from its orbit. The two smaller companions are Polaris B, a 1.39 M☉ F3 main-sequence star orbiting at a distance of 2400 astronomical units (AU),[citation needed] and Polaris Ab (or P), a very close F6 main-sequence star with a mass of 1.26 M☉.

Polaris B can be seen with a modest telescope. William Herschel discovered the star in August 1779 using a reflecting telescope of his own, one of the best telescopes of the time. By examining the spectrum of Polaris A, it was also discovered in 1929 that it was a very close binary, with the secondary being a dwarf (variously α UMi P, α UMi an or α UMi Ab), which had been theorized in earlier observations (Moore, J. H. and Kholodovsky, E. A.). In January 2006, NASA released images, from the Hubble telescope, that showed the three members of the Polaris ternary system.[11][12]

There were once thought to be two more distant components—Polaris C and Polaris D—but these have been shown not to be physically associated with the Polaris system.[10][13]

Observation[edit]

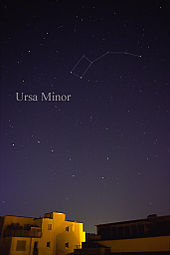

Polaris is the brightest star in the constellation of Ursa Minor (upper right).

Polaris is the brightest star in the constellation of Ursa Minor (upper right). Big Dipper and Ursa Minor in relation to Polaris

Big Dipper and Ursa Minor in relation to Polaris A typical Northern Hemisphere star trail with Polaris in the center.

A typical Northern Hemisphere star trail with Polaris in the center. A view of Polaris in a small telescope. Polaris B is separated by 18 arc seconds from the primary star, Polaris A.

A view of Polaris in a small telescope. Polaris B is separated by 18 arc seconds from the primary star, Polaris A.Variability[edit]

Polaris Aa, the supergiant primary component, is a low-amplitude Population I classical Cepheid variable, although it was once thought to be a type II Cepheid due to its high galactic latitude. Cepheids constitute an important standard candle for determining distance, so Polaris, as the closest such star, is heavily studied. The variability of Polaris had been suspected since 1852; this variation was confirmed by Ejnar Hertzsprung in 1911.[14]

The range of brightness of Polaris during its pulsations is given as 1.86–2.13,[3] but the amplitude has changed since discovery. Prior to 1963, the amplitude was over 0.1 magnitude and was very gradually decreasing. After 1966 it very rapidly decreased until it was less than 0.05 magnitude; since then, it has erratically varied near that range. It has been reported that the amplitude is now increasing again, a reversal not seen in any other Cepheid.[2]

The period, roughly 4 days, has also changed over time. It has steadily increased by around 4.5 seconds per year except for a hiatus in 1963–1965. This was originally thought to be due to secular redward evolution across the Cepheid instability strip, but it may be due to interference between the primary and the first-overtone pulsation modes.[12][15][16] Authors disagree on whether Polaris is a fundamental or first-overtone pulsator and on whether it is crossing the instability strip for the first time or not.[7][16][17]

The temperature of Polaris varies by only a small amount during its pulsations, but the amount of this variation is variable and unpredictable. The erratic changes of temperature and the amplitude of temperature changes during each cycle, from less than 50 K to at least 170 K, may be related to the orbit with Polaris Ab.[8]

Research reported in Science suggests that Polaris is 2.5 times brighter today than when Ptolemy observed it, changing from third to second magnitude.[18] Astronomer Edward Guinan considers this to be a remarkable change and is on record as saying that "if they are real, these changes are 100 times larger than [those] predicted by current theories of stellar evolution".

Role as pole star[edit]

Main article: Pole starBecause Polaris lies nearly in a direct line with the Earth's rotational axis "above" the North Pole—the north celestial pole—Polaris stands almost motionless in the sky, and all the stars of the northern sky appear to rotate around it. Therefore, it makes an excellent fixed point from which to draw measurements for celestial navigation and for astrometry. The moving of Polaris towards and, in the future, away from the celestial pole, is due to the precession of the equinoxes.[19] The celestial pole will move away from α UMi after the 21st century, passing close by Gamma Cephei by about the 41st century, moving towards Deneb by about the 91st century. The celestial pole was close to Thuban around 2750 BC,[19] and during classical antiquity it was closer to Kochab (β UMi) than to Polaris.[20] It was about the same angular distance from β UMi as to α UMi by the end of late antiquity. The Greek navigator Pytheas in ca. 320 BC described the celestial pole as devoid of stars. However, as one of the brighter stars close to the celestial pole, Polaris was used for navigation at least from late antiquity, and described as ἀεί φανής (aei phanēs) "always visible" by Stobaeus (5th century), and it could reasonably be described as stella polaris from about the High Middle Ages. In Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, written around 1599, Caesar describes himself as being "as constant as the northern star", though in Caesar's time there was no constant northern star.

Polaris was referenced in Nathaniel Bowditch's 1802 book, American Practical Navigator, where it is listed as one of the navigational stars.[21] Twice in each sidereal day Polaris' azimuth is true north; the rest of the time it is displaced eastward or westward, and the bearing must be corrected using tables or a rule of thumb. The best approximation[22] was made using the leading edge of the "Big Dipper" asterism in the constellation Ursa Major. The leading edge (defined by the stars Dubhe and Merak) was referenced to a clock face, and the true azimuth of Polaris worked out for different latitudes.

Names[edit]

This artist's concept shows: supergiant Polaris Aa, dwarf Polaris Ab, and the distant dwarf companion Polaris B.

This artist's concept shows: supergiant Polaris Aa, dwarf Polaris Ab, and the distant dwarf companion Polaris B.The modern name Polaris[23] is shortened from New Latin stella polaris "polar star", coined in the Renaissance era, when the star had approached the celestial pole to within a few degrees. Gemma Frisius, writing in 1547, referred to it as stella illa quae polaris dicitur ("that star which is called 'polar'"), placing it 3° 8' from the celestial pole.[24]

In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[25] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[26] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN; which included Polaris for the star α Ursae Minoris Aa.

In antiquity, Polaris was not yet the closest naked-eye star to the celestial pole, and the entire constellation of Ursa Minor was used for navigation rather than any single star. Polaris moved close enough to the pole to be the closest naked-eye star, even though still at a distance of several degrees, in the early medieval period, and numerous names referring to this characteristic as polar star have been in use since the medieval period. In Old English, it was known as scip-steorra ("ship-star"); In the Old English rune poem, the T-rune is apparently associated with "a circumpolar constellation", compared to the quality of steadfastness or honour.[27]

In the Hindu Puranas, it became personified under the name Dhruva ("immovable, fixed").[28] In the later medieval period, it became associated with the Marian title of Stella Maris "Star of the Sea" (so in Bartholomeus Anglicus, c. 1270s)[29] An older English name, attested since the 14th century, is lodestar "guiding star", cognate with the Old Norse leiðarstjarna, Middle High German leitsterne.[30]

The ancient name of the constellation Ursa Minor, Cynosura (from the Greek κυνόσουρα "the dog’s tail" ) became associated with the pole star in particular by the early modern period. An explicit identification of Mary as stella maris with the polar star (Stella Polaris), as well as the use of Cyonsura as a name of the star, is evident in the title Cynosura seu Mariana Stella Polaris (i.e. "Cynosure, or the Marian Polar Star"), a collection of Marian poetry published by Nicolaus Lucensis (Niccolo Barsotti de Lucca) in 1655.[citation needed]

In the Tuareg Berber language in North Africa the North Star is known as "Tatrit tan Tamasna" which means: "star of the plains" or "star of the desert" and that indicates its central role in navigating the vast deserts.[citation needed]

Its name in traditional pre-Islamic Arab astronomy was Al-Judeyy الجدي, and that name was used in medieval Islamic astronomy as well.[31][32] In those times, it was not yet as close to the north celestial pole as it is now, and used to rotate around the pole.

It was invoked as a symbol of steadfastness in poetry, as "steadfast star" by Spenser. Shakespeare's sonnet 116 is an example of the symbolism of the north star as a guiding principle: "[Love] is the star to every wandering bark / Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken." In Julius Caesar, he has Caesar explain his refusal to grant a pardon by saying, "I am as constant as the northern star/Of whose true-fixed and resting quality/There is no fellow in the firmament./The skies are painted with unnumbered sparks,/They are all fire and every one doth shine,/But there’s but one in all doth hold his place;/So in the world" (III, i, 65–71). Of course, Polaris will not "constantly" remain as the north star due to precession, but this is only noticeable over centuries.[citation needed]

In Inuit astronomy, Polaris is known as Niqirtsuituq. It is depicted on the flag and coat of arms of the Canadian Inuit territory of Nunavut, as well as on the flag of the U.S. state of Alaska.[33]

Distance[edit]

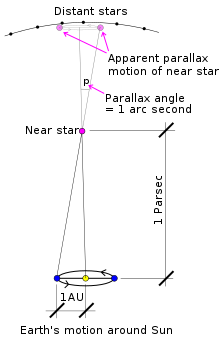

Stellar parallax is the basis for the parsec, which is the distance from the Sun to an astronomical object which has a parallax angle of one arcsecond. (1 AU and 1 pc are not to scale, 1 pc = about 206265 AU)

Stellar parallax is the basis for the parsec, which is the distance from the Sun to an astronomical object which has a parallax angle of one arcsecond. (1 AU and 1 pc are not to scale, 1 pc = about 206265 AU)Many recent papers calculate the distance to Polaris at about 433 light-years (133 parsecs),[12] in agreement with parallax measurements from the Hipparcos astrometry satellite. Older distance estimates were often slightly less, and recent research based on high resolution spectral analysis suggests it may be up to 110 light years closer (323 ly/99 pc).[6] Polaris is the closest Cepheid variable to Earth so its physical parameters are of critical importance to the whole astronomical distance scale.[6] It is also the only one with a dynamically measured mass.

| Year | Component | Distance, ly (pc) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | A | 330 ly (101 pc) | Turner[15] |

| 2007[A] | A | 433 ly (133 pc) | Hipparcos[5] |

| 2008 | B | 359 ly (110 pc) | Usenko & Klochkova[4] |

| 2013 | B | 323 ly (99 pc) | Turner, et al.[6] |

| 2014 | A | ≥ 385 ly (≥ 118 pc) | Neilson[34] |

| 2018 | B | 521 ly (160pc) | Bond et al.[35] |

| 2018 | B | 445.3 ly (136.6 pc)[A] | Gaia DR2[36] |

| A New revision of observations from 1989–1993, first published in 1997 |

| B Statistical distance calculated using a weak distance prior |

The Hipparcos spacecraft used stellar parallax to take measurements from 1989 and 1993 with the accuracy of 0.97 milliarcseconds (970 microarcseconds), and it obtained accurate measurements for stellar distances up to 1,000 pc away.[37] The Hipparcos data was examined again with more advanced error correction and statistical techniques.[5] Despite the advantages of Hipparcos astrometry, the uncertainty in its Polaris data has been pointed out and some researchers have questioned the accuracy of Hipparcos when measuring binary Cepheids like Polaris.[6] The Hipparcos reduction specifically for Polaris has been re-examined and reaffirmed but there is still not widespread agreement about the distance.[38]

The next major step in high precision parallax measurements comes from Gaia, a space astrometry mission launched in 2013 and intended to measure stellar parallax to within 25 microarcseconds (μas).[39] Although it was originally planned to limit Gaia's observations to stars fainter than magnitude 5.7, tests carried out during the commissioning phase indicated that Gaia could autonomously identify stars as bright as magnitude 3. When Gaia entered regular scientific operations in July 2014, it was configured to routinely process stars in the magnitude range 3 – 20.[40] Beyond that limit, special procedures are used to download raw scanning data for the remaining 230 stars brighter than magnitude 3; methods to reduce and analyse these data are being developed; and it is expected that there will be "complete sky coverage at the bright end" with standard errors of "a few dozen µas".[41] Gaia Data Release 2 does not include a parallax for Polaris, but a distance inferred from it is 136.6±0.5 pc (445.5 ly) for Polaris B,[36] somewhat further than most previous estimates and several times more accurate.

Polaris has long been important for the cosmic distance ladder because, prior to Gaia, it was the only Cepheid variable for which direct distance data existed, which had a ripple effect on distance measurements that use this "ruler".[42]

Observational history[edit]

| Source | Presence |

|---|---|

| Ptolemy (~169) | Yes |

| Al-Sufi (964) | Yes |

| Al-Biruni (~1030) | Yes |

| Khayyam (~1100) | Yes |

| Nasir al-Din al-Tusi (1272) | No |

| Ulugh Beg (1437) | Yes |

| Copernicus (1543) | Yes |

| Schöner (1551) | Yes |

| Brahe (1598) | Yes |

| Brahe (1602) | Yes |

| Bayer (1603) | Yes |

| De Houtman (1603) | No |

| Kepler (1627) | Yes |

| Schiller (1627) | Yes |

| Halley (1679) | No |

| Hevelius (1690) | Yes |

| Flamsteed (1725) | Yes |

| Flamsteed (1729) | Yes |

| Bode (1801a) | Yes |

| Bode (1801b) | Yes |